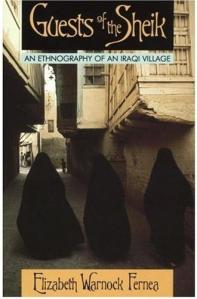

Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, the pioneering scholar of Arab women and the Middle East, has died. We reviewed her excellent Guests of the Sheikh here last month. The Los Angeles Times has a sympatheic obituary:

[W]hen she left [the Iraqi village of El Nahra] two years later, she had won over the women and the village with her efforts to learn their language and culture.

In “500 Great Books by Women” (1994), reviewer Rebecca Sullivan wrote, “The story of her life among the Iraqis is eye-opening, written with intellectual honesty as well as love and respect for the seemingly impenetrable society.”

Here is Guests of the Sheikh on Amazon, and here is the quasi-sequel, The Arab World. Here are her pages on Librarything and Wikipedia. Dr. Fernea wrote several books about women and Arab society and served as director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas.

I spend some of my time in the rural areas south of metropolitan Baghdad. Dr. Fernea’s book, which I read only a few weeks ago, opened a vital window onto rural Iraqi society. Its acute observation and spare prose make it an American classic, like Dr. Fernea herself.